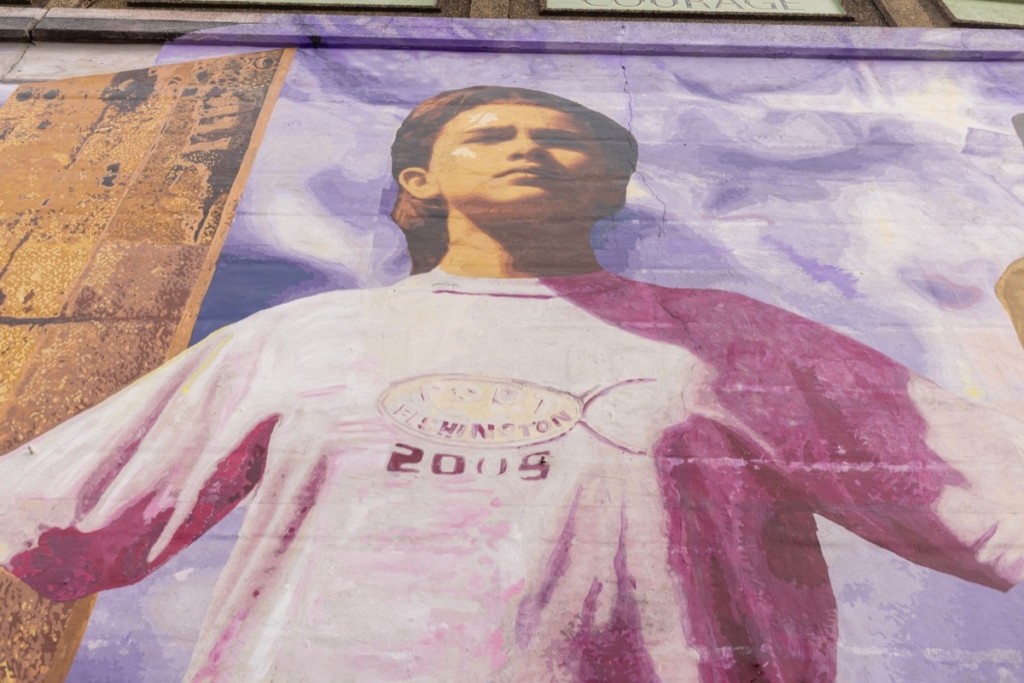

On East Lehigh Avenue, a long mural stretches across a bridge wall, unfolding like a slow-moving film. Painted in 2005, “My Life, My Path, My Destiny” is not a single image but a sequence of moments — choices, missteps, hopes, and transformations — rendered across a span of the neighborhood. This mural depicts the human life cycle from infancy to adulthood. In the middle, there is an image of a child caught in a Venus flytrap, which represents “pressure” and the “lure of drugs and easy money,” according to Mural Arts Philadelphia’s written description. Created by the Philadelphia muralist Cesar Viveros with the involvement of at-risk male youth from St. Gabriel’s Hall, incarcerated men, and local residents, the mural remains one of the most ambitious narrative works in Philadelphia’s public art landscape. This mural was made possible by conversations with the community — knocking on doors and putting up flyers to get the word out about the project, carrying it from seedling to flourishing sapling to a fully grown tree.

For the Mexican-born artist, murals have never been about decoration. “Murals are like a movie,” he says. “They record what happened at the time.” When he began working on “My Life, My Path, My Destiny,” pockets of the neighborhoods that surround the mural — Kensington, Fishtown, and Port Richmond — were grappling with economic pressure, generational poverty, and limited opportunities for young people. The mural was conceived as a space to confront those realities without flattening them, holding complexity rather than prescribing solutions. It reflects our decisions through life, how they have shaped our past and ultimately lead to our destiny. It encourages the viewers to reflect on their own lives and think about the decisions they’ve made to bring them to where they are.

The project, which was initiated by Mural Arts Philadelphia, was conceived as a process-based project. The goal was to develop a mural design that reflected the concerns, experiences, and hopes of the different communities involved, with a special emphasis on young voices. Another aim was to use the act of designing and painting the mural as a way to create dialogue, understanding, and connection among participants. The project brought together teenage boys from St. Gabriel’s Hall, a faith-based residential treatment facility for male youth, incarcerated men from Graterford Prison, and youth from the surrounding neighborhoods as well as community members, advocates of victims, and family and advocates of inmates. For Viveros, this convergence of people from varying backgrounds was essential. In a neighborhood like Kensington, “paths constantly intersect, influence one another, and sometimes clash, but they also create the possibility for understanding and collective healing,” Viveros says.

Getting this project underway was “as simple as grabbing a brush and being expressive with painting,” he explains, adding that the act of painting made a difference in their lives. Painting together created a rare environment where young people from radically different circumstances could coexist, collaborate, and see one another beyond labels imposed by the justice system or geography. These groups of individuals painted on the same panels — 240 5’ x 5’ fabric panels traced by the artist. Bringing their brushstrokes together in the same place represented a coming together of different communities for one greater meaning. “I purposefully had all the groups paint on some panels just to make a symbolic physical connection between them,” Viveros explained.

Some participants painted their own portraits. Others posed for photographs that were later translated into monumental figures. “Some of them were actually painting their own portrait and seeing themselves larger than life in a permanent piece,” Viveros recalls. “In a way, it made them proud of being part of this history.” Two decades later, the mural still holds those faces, preserving a moment in time that represented the past, present, and future; when possibility felt fragile but real; when recognition itself carried weight.

“At the end of the day,” Viveros says, a person’s path “is a matter of decisions.” This belief — that redemption is possible, that paths can change — anchors the mural’s emotional arc. In conversations between incarcerated men and teenagers, Viveros witnessed the gravity of lived consequence. “These kids still have a second chance,” he says. “They can avoid prison and become something else.” Over the years, he has encountered former participants who have done just that — building careers, families, and creative lives that extended far beyond what was once expected of them. Once, at a flea market, Viveros ran into a man who was proud to tell him he has just been accepted into the Army. He said when he drove around those streets with family and friends, he always boasted that he’d worked on the mural. Two of the girls depicted in the mural are now executives.

Born in Veracruz, Mexico, Viveros grew up immersed in the legacy of Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco. “They were able to find heroes among average people,” he says. “The worker, the working class.” Their influence informs “My Life, My Path, My Destiny,” in which everyday figures become protagonists in a moral and emotional narrative about choice, responsibility, and dignity.

The mural confronts uncomfortable truths. Scenes of family, care, and encouragement — a grandfather holding his grandchild, a female teenager with her hands over her chest and her womb, another teenager with her arms outstretched like a bird — are punctuated by darker imagery — temptation, confinement, and risk — motifs of drugs and easy money. One of the mural’s most striking metaphors is a Venus flytrap, which is overlaid near faces of teenagers. “It’s attractive, sweet, and then it traps you,” Viveros explains. For him, the plant embodies the dangers facing teenagers without guidance, exposed to systems that promise escape but deliver confinement instead. Yet this is a piece that challenges fatalistic views. Adult figures emerge from the Venus flytrap. A door which was once closed is now open. Books appear. Bodies lean forward, arms stretched upward, hands over hearts.

The mural is also deeply tied to place. The intersection where it lives marks the meeting point of multiple neighborhoods and identities. Rather than naming each one explicitly, the youth involved claimed the overlap itself as a symbol — evidence that difference doesn’t mean you don’t belong. “Every voice is diverse,” Viveros says. “Everyone can contribute with their own personality.” The wall became a shared surface where individuality and collectivity could exist at once.

Looking back 20 years later, Viveros sees the mural as both a document and a prophecy. The people who participated in the creation of the mural “kind of saw the future,” he reflects — imagining cleaner streets, safer spaces, and new generations reshaping the neighborhood. Today, as the area continues to change under the pressures of development and displacement, the mural stands as a reminder that transformation is neither simple nor neutral. It is built from countless personal decisions, shaped by systems larger than any one individual.

Since completing “My Life, My Path, My Destiny,” Viveros’s practice has included sculpture, performance, and installations rooted in Indigenous and Mesoamerican traditions. Yet the core of his mission remains unchanged. “I want to create spaces where people feel safe,” he says, “where my community can thrive.” He adds, “Whether it’s a garden, a wall, or an open lot, I treat each space as a living social site — one that asserts dignity, challenges erasure, and makes immigrant communities visible in places where they are often pushed to the margins.”

Viveros describes his work as a root transplanted into new soil — Mexican traditions growing within Philadelphia’s urban landscape. “My Life, My Path, My Destiny” is one of the clearest expressions of that vision: that you are in charge of your own destiny. It asks all viewers — especially young ones — to recognize themselves in its figures and to consider, with honesty and hope, the paths still open before them.